Dear all, it is time for the second newsletter on mental health among doctoral researchers and mental health in science in general. In case you missed the first one, catch up here.

This time, we are talking about the statistics. What does the data show regarding mental health in academia and research? How is the Helmholtz Association doing on the topic of mental health, according to the 2019 survey? We wrap up with pointing to some common stressors: how to recognize them in others and ourselves; as well as how to help those who experience these stressors. Last, but not least, we invite you to share your opinions and ideas. Enjoy reading!

Mental Health – Why do we care?

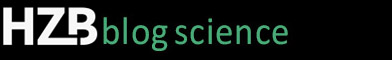

The mental health of Doctoral Researchers has been increasingly analyzed during the last years, often with alarming results. Major concerns regarding the well-being of early career researchers are depression, anxiety, harassment and a difficult work-life balance.

The mental health of Doctoral Researchers has been increasingly analyzed during the last years, often with alarming results. Major concerns regarding the well-being of early career researchers are depression, anxiety, harassment and a difficult work-life balance.

What do studies say?

- The Graduate Assembly (2014) reported that 47% of Doctoral Researchers of the University of California, Berkeley met the threshold for depression.

- A study by Levecque et al. (2017) analyzed the situation of more than 3000 Doctoral Researchers in Belgium and found that 32% of Doctoral Researchers are at risk of a common psychiatric disorder, such as depression, which makes the risk for psychiatric disorders in academia higher than in other highly-educated groups. Main reasons were work-family interfaces, job demands and job control, and the leadership style of the supervisor (Levecque et al., 2017).

- In a Nature study (Woolston, 2017), 29% of 5700 Doctoral Researchers listed mental health as an area of concern, with half of them getting help for depression or anxiety caused by their PhD study.

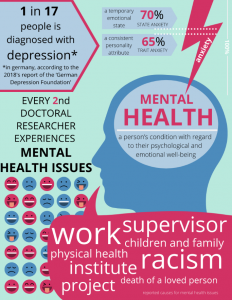

- A follow-up Nature study in 2019 showed that things seem to get worse; 36% of 6300 PhDs from all around the globe seeking help for depression and anxiety related to their PhD project. Also, one-fifth reported bullying, while another fifth experienced discrimination or harassment (Nature, 2019).

- The EPFL Doctoral III survey (2019) draws a similar image:

- 7% of the 1043 participating Doctoral Researchers experienced bullying or behaviours that may constitute as bullying, which includes aggressive behaviour, being undermined and being isolated and ignored by people at work. If there is evidence of bullying, more than 90% of respondents showed depressive symptoms (EPFL, 2019).

- Another reason for the critical mental health situation is that success is measured in publications, citations, funding and impact. The autonomy of research is reduced or removed when funding, publications and impact are part of the universities formal monitoring and evaluation system, and when supervisors judge the failure or success of Doctoral Researchers (Nature, 2019).

What did we find?

During the 2019 Helmholtz Juniors survey, we tried to get an overview of the mental health of all Doctoral Researchers within the Helmholtz Association. The survey used a shortened STAI questionnaire.

During the 2019 Helmholtz Juniors survey, we tried to get an overview of the mental health of all Doctoral Researchers within the Helmholtz Association. The survey used a shortened STAI questionnaire.

- The high number of working hours – 66 % work more than 41h while even 18 % work more than 50h a week – and high conflict potential – 16 % reported conflicts with superiors are critical influences on the mental health of young Doctoral Researchers.

- Analysis of the questionnaire indicated 22% showed signs of moderate to severe depression and 70% showed signs of moderate to high state anxiety.

The results are, sadly, similar to the findings of the already presented studies. The first step in finding solutions and ways to tackle a problem is knowing about it in the first place!

Other than working on various strategies, we – the Helmholtz Juniors and the Team of Doctoral Representatives at HZB – believe that it is also important to recognize the possible stressors and signs of stress as early as possible, before they escalate in mental health challenges like anxiety and depression.

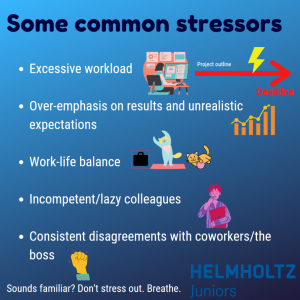

Stressors for PhD students

Stressors can be various, but for Doctoral Researchers, it mostly starts with a high workload and high expectations – which potentially activate a downwards spiral. This can lead to less time for hobbies (friends, sports etc.), which can be leading to sleeplessness and therefore tiredness and in the end potentially social isolation. Everyone deals with stress differently: some seem pretty robust when it comes to stress – mainly because they´ve learned how to personally deal with stress; while some seem very prone to stress and react with severe psychological as well as physiological symptoms. However, no matter how well we deal with stress, in the end, nobody is immune to it.

People tend to overlook these early signs or do not take them seriously. We think that in a few days everything will be fine again. A more worrying thought is that many of us equate our work performance to our self-worth. Namely, we think they need to function non-stop, or otherwise they are worthless.

People tend to overlook these early signs or do not take them seriously. We think that in a few days everything will be fine again. A more worrying thought is that many of us equate our work performance to our self-worth. Namely, we think they need to function non-stop, or otherwise they are worthless.

Often, these signs last – and we slowly start getting used to them. However, the stress itself is still there and the signs of stress get worse. At some point, they might even lead to the burnout syndrome. Therefore, it is very useful to learn which signs of stress we are experiencing. Knowing our personal symptoms already helps to prevent further stress and prevent letting it slip and get worse.

Additionally, by increasing our knowledge in this topic, we might be able to identify such signs in our colleagues who might be eager to have someone understand what they are going through. This is especially welcomed when done by supervisors and professors, who encourage their students with acknowledgement for their work, but also with an advice that being stressed is not a sign of weakness and that it is okay to need a break!

Dear doctoral researchers, dear supervisors, dear professors, please remember that a non-stressed researcher is way more productive than a completely stressed-out one.

We would like to hear your opinion!

What do you think are the biggest challenges for keeping a good mental health while doing a PhD or being in science in general? Have you encountered a hostile workplace atmosphere and if yes, how did you deal with it? Do you want to help us create a more sustainable work environment in academic research? We would love to hear your thoughts and ideas!

All the best!

Your local Helmholtz Juniors

Marlene Härtel and Ivona Kafedjiska

And Doctoral Representatives: Radu Bors, Markus Schleuning, Patrick Schnell, Jennifer Velázquez Rojas, Ke Xu, Ivona Kafedjiska, Marlene Härtel

Follow us and keep up2date with our work!

https://www.helmholtz.de/karriere_talente/wissenschaft/promovierende/helmholtz_juniors/

https://www.facebook.com/helmholtz.juniors/

https://www.instagram.com/helmholtz.juniors/

https://twitter.com/helmholtzjrs/

Authors: Nicolas Stoll (AWI), Fabian Wolf (GEOMAR), Pedro Ivo Silva Batista (DESY), Martin Schrader (HZDR), Michaela Löffler (UFZ), Younes Bouhadjar (FZJ), Stephanie Taylor (DZNE), Khwab Sanghvi (DKFZ), Lukas Kreis (GSI), Johannes Nelles (UFZ), Vasundhra Shaw (DESY), Olya Oppenheim (MDC)

Design: Marlene Härtel (HZB), Martin Schrader (HZDR), Anna-Lena Amend (HMGU), Xin You (UFZ)

Edited by: Ivona Kafedjiska (HZB)