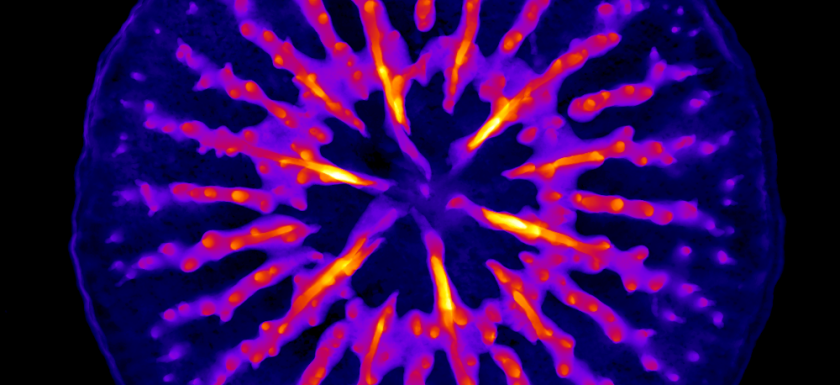

A few weeks ago, I discovered utterly beautiful pictures in our Twitter timeline: filigree, radially symmetrical structures that looked like art objects. They were tiny corals that had just formed their first skeleton. The pictures had been taken at the BAMline at BESSY. They triggered my curiosity and I contacted the scientist who had posted them. Federica Scucchia replied right away and we arranged to meet next time she would be in Berlin.

Federica is currently doing her PhD in Haifa, Israel, on the effects of climate change and ocean acidification on coral growth. In Berlin, she is working with Paul Zaslansky, a materials researcher and dentist at the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin: Paul is a regular guest at BAMline, where he takes high-resolution 3D images of tooth roots in order to compare different treatment options. His research interests are wide, he also examines fish teeth and other biominerals or bone-like materials. I met Federica at Paul Zaslansky’s lab in the south of Berlin.

Harvesting fresh baby corals

Federica studied marine biology in Bologna, Italy and did part of her Master’s studies in California. Then she applied for a PhD position at Tali Mass in Haifa, Israel. “Tali has built a fantastic lab in Haifa and we have a research station in Eilat by the red sea,” she told me. That’s where she particularly likes to be, diving down in a wetsuit and collecting fresh “baby corals” that have landed in special collector bags. She has a diving licence, with the qualification to do underwater research.

The harvested specimens are then placed in saltwater aquariums where they grow and form their skeletons. “In the process, we can precisely adjust the acidity of the water as well as the temperature, and thus also produce the future conditions for corals – taking a glimpse into the future,” she explains.

The threat: Ocean acidification

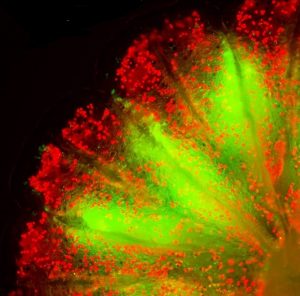

Corals are not plants, but belong to the animal kingdom. They are made of many tiny polyps surmounted by a crown of tentacles. With these, they take ions from the water and gradually build an almost radially symmetrical skeleton. These fascinating organisms often unite to form large structures, the coral reefs. They filter microplankton and other nutrients from the sea, and can live in symbiosis with colourful algae, which contribute to the reef’s nutrition via photosynthesis. Climate change is particularly hard on the stony corals. With rising CO2 in the atmosphere, also the oceans have to absorb more CO2, resulting in the formation of carbonic acid, which attacks structures made of calcium carbonate such as shells, but also corals. This is referred to as ocean acidification.

Corals are not plants, but belong to the animal kingdom. They are made of many tiny polyps surmounted by a crown of tentacles. With these, they take ions from the water and gradually build an almost radially symmetrical skeleton. These fascinating organisms often unite to form large structures, the coral reefs. They filter microplankton and other nutrients from the sea, and can live in symbiosis with colourful algae, which contribute to the reef’s nutrition via photosynthesis. Climate change is particularly hard on the stony corals. With rising CO2 in the atmosphere, also the oceans have to absorb more CO2, resulting in the formation of carbonic acid, which attacks structures made of calcium carbonate such as shells, but also corals. This is referred to as ocean acidification.

Hope for coral reefs

With the high-resolution three-dimensional computer tomographies she obtains at BAMline of her baby corals, Federica can analyse exactly how acidification affects the formation of the coral skeleton. “Processing and analysing these enormous amounts of data is not easy, but I hope to learn a lot from these highly precise imaging, especially thanks to the expert guidance of Dr. Zaslansky”, she admits.

What does she think about the future? Is there still hope for coral reefs? “There always has to be hope,” she says. “It might be possible that certain types of coral will cope better with the new conditions than others – but the most important thing, of course, is to get greenhouse gas emissions down as quickly as possible to limit the damage.”

Read more about the collaboration:

Read more about the collaboration:

Follow Federica Scucchia on Twitter: @FedeScucchia