By summerstudent Fernando Alonso Cordova Mariño >

In recent years, science in my country, Peru, has begun to gain relevance. More and more young people are drawn to scientific careers, motivated by curiosity and a passion for continuing to learn. However, those of us who decide to take this path know it’s not easy. Limited infrastructure, funding, and recognition have been constant obstacles to growth.

I remember a phrase a professor told us in the first years of university: “We have to learn to do science with sticks, ropes, and stones.” He wasn’t just referring to the lack of resources, but also to the creativity and determination with which we face challenges. Doing science in Latin America often requires ingenuity more than sophisticated equipment.

Sticks, ropes and stones

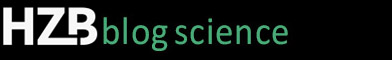

A common habit among young scientists in Peru is excessive comparison. Admiration for other great laboratories around the world, whether for their technological advances or the scope of their impact, led to the perception of an overwhelming gap in knowledge or skills. Although I may not agree with it, this experience abroad helped me understand and further break down that notion. When I arrived here at the laboratory of HZB, the first thing that surprised me was how familiar everything felt. During the safety and induction sessions, I recognized equipment like the ellipsometer and the UV-VIS spectrophotometer, which I had worked with before. It felt natural to integrate and operate the machines safely, even with a certain degree of mastery. I realized that the training I received in Peru had been sufficient to function comfortably in a high-level environment.

I also had the opportunity to visit and experiment in laboratories with more specialized electron spectrophotometry was performed without breaking the vacuum. Although I’m new to ESP, the ultra-high vacuum (UHV) system is related to my knowledge, such as pressure management, differentiated chambers, energy used… All of this felt understandable and relatable.

Beyond the laboratories, one of the most interesting aspects was talking with the other international students. Although each of us had our own project, the scientific language and prior experience allowed us to exchange ideas, ask questions, and give each other feedback, even if only superficially. Everything indicated that, despite coming from different places, we spoke the same language.

This experience has been, in many ways, a breath of fresh air. Leaving one’s comfort zone and facing a new environment helps dismantle internal and external prejudices. Because no, there is no intellectual disadvantage. Talent and ability are equally distributed; what isn’t always equal are the opportunities. And yet, from our contexts, we continue to demonstrate that quality science can be done, even with sticks, ropes, and stones.

About the author: Fernando Alonso Cordova Mariño is a master’s student at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (PUCP). He is an active member of the Materials and Renewable Energies research group (MatER-PUCP) and works with transparent conducting oxides (TCOs). Currently, he is participating in the HZB summer programme under the supervision of Dr. Lars Korte. His project is titled: “Relationship between Doping, and Optoelectronic and Structural Properties of TCOs Using XPS and UPS”.